The Free-Range Bookclub

Bookclubbers without boundaries in Nelson, New Zealand

Love is Blind – William Boyd

READ FOR BOOKCLUB

Chosen by Sally

Brodie Moncur is a young Scottish piano tuner who moves to Paris for a job and to escape his tyrannical father. There, a fateful encounter with a famous pianist changes his future and sparks an obsessive love affair with a beautiful Russian soprano. Moving between Paris, St Petersburg and Edinburgh in the early 20th century, Brodie’s love and its dangerous consequences pursue him around Europe and beyond.

“Complications. Oh, yes.’ The doctor reflected and then said, ‘I always think a life without complications isn’t really a life, you know. In life things go wrong, nothing stays the same and there’s nothing you can do about it. Friends betray you, family is a nightmare, lovers are fickle. This is the norm, no?’

SALLY:

● This was my choice for book group, having enjoyed some of Boyd’s previous work and wishing to introduce this Scottish author to my book group friends.

The book is in the style of others that I have read of his, in that it follows the life of an everyman character throughout whichever period of history and setting Boyd has chosen. He is meticulously researched and drills down into the minutiae of his characters lives as well accurate historical fact. He frequently blends real life characters into the plot with his fictional characters. Boyd himself has written “It’s the haphazard, rollercoaster of a life that is the key in the whole-life novel rather than a particular plot, theme or central relationship. Everything is grist to the mill for such novels, and this is what distinguishes the type.”

The story of Brodie Moncur’s life and undimmed love for Lika flows from Scotland to Paris, St Petersburg, Trieste and finally the South Pacific. Whilst I could be persuaded by Brodie’s emotion for Lika, I was never fully convinced of her’s for him, and I had a mild unease throughout the book that she was not quite what she seemed. Considering that, I found the ending slightly far-fetched.

Of all the Boyd novels I have read, this one seemed to be the bleakest. Possibly because of the number of betrayals Brodie suffers, possibly because the Scottish settings and characters are so mean (and I say this as a Scot). Happily, this has not put my book club friends off and one at least has read another Boyd subsequently. Mission accomplished!

JODIE:

● Love Is Blind starts strongly, with an original premise and some genuinely interesting detail about piano tuning, which I enjoyed. The early chapters drew me in and promised a rich, atmospheric historical novel.

However, the second half felt drawn out, repetitive, and slow. The drama often tipped into melodrama, without enough emotional depth to support it. Considering the book’s settings – Edinburgh, Paris, the French Riviera – I found the scenes surprisingly underdeveloped. I never gained a strong sense of place, which felt like a missed opportunity. I also struggled to believe in the characters, who seemed thinly drawn. As a result, the ending was anticlimactic rather than moving.

Overall, it’s a good storyline with an intriguing musical angle, but for me the execution fell short of its potential.

TESSA:

● After finishing Love Is Blind by William Boyd, I was left with mixed feelings. On one hand I really enjoyed the setting. Boyd brings to life the world of music halls, touring virtuosi and piano tuning with rich, convincing detail. The precarious livelihoods of musicians, the craft of tuning itself, all of it feels immersive and authentic. The historical backdrop is beautifully realised, and it’s clear how much care has gone into recreating this musical world.

But for me, I found the main characters difficult to warm to and struggled to invest in their relationship. Brodie often feels more like an observer than a fully realised emotional presence, and Lika remains frustratingly elusive. Overall, it felt muted and somewhat disappointing and the ending struck me as unsatisfying.

RACHEL:

● First of all, I think the cover and title do this book a disservice. It presents as a straightforward romance and, yes, while a love story does sit at its centre, Love Is Blind is more than that. It’s historical fiction, set in Scotland, France, Russia and other European outposts, and is the life story of an ordinary man (as ordinary as a piano tuner who engages in gun-toting duels can be). If you like music and European history, this may appeal to you.

Personally, I had mixed feelings. In hindsight, I appreciated the full life story, but while reading I did not because I kept trying to assign meaning to everything, wondering what purpose each event served. As Sally pointed out at bookclub, some things did not have a higher purpose, they were included simply because these things happen in real life. I suspect I might have enjoyed it more if I had a better understanding of the book from the outset. Ultimately I found it slow to start, some characters frustrating, and the ending a bit ridiculous. Though I did enjoy some of the mid-book action-packed scenes. Another bugbear was the presentation of women, their descriptions, thoughts and actions. To me it was apparent they were written by a man and I found myself eye-rolling a bit.

BRIDGET

● William Boyd proves himself a remarkably skillful wordsmith in this life genre, where obsession, betrayal, and revenge drive the narrative forward. At the centre of this book is Brodie, a man who finds himself betrayed by his employer and the woman he loves. Brodie is a pleasant enough character but I found I him, at times, weak and I really wanted him to make better decisions. I felt Lika, Brodie’s love interest, could have been more fully developed. Her elusiveness creates a sense that she is never entirely present, always holding something back. Perhaps that intentional distance is essential to her character, but it still left me wanting a deeper connection to her.

I was disappointed with the conclusion, it felt a little undercooked and I found myself wishing for something with a bit more of a punch to it. Love is Blind was an easy read if not a little boring. I would recommend it to anyone interested in the workings of pianos.

Published 2018

Alfred A. Knopf

384 pages

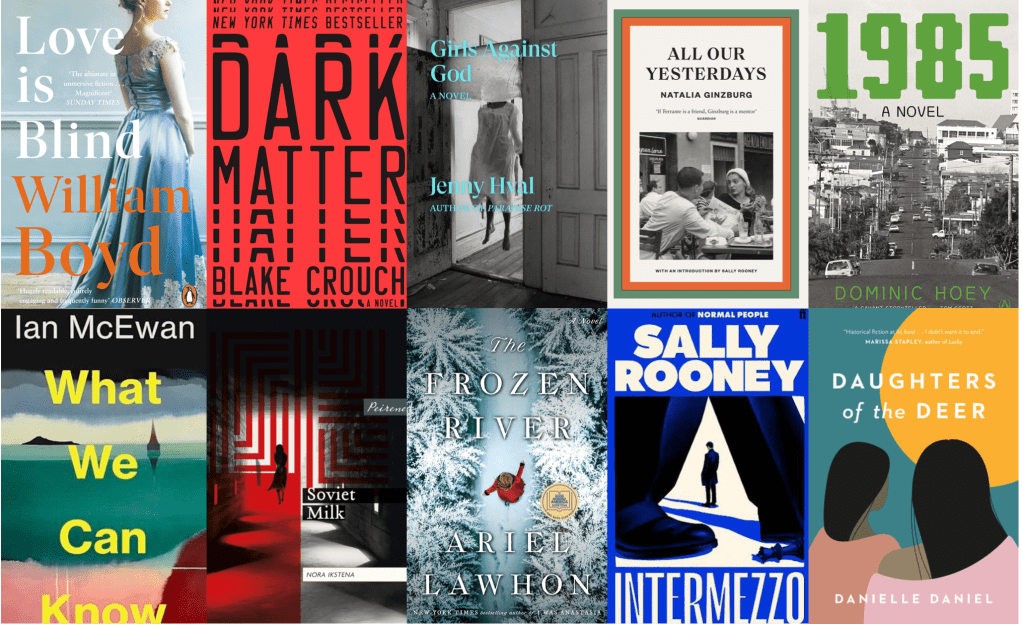

2026: Timelines

In 2026 we are focused on the intersection of time, or what do we owe the past, and what do we owe the future? We have a new and evolving bookclub that is considerate of the past members and reading history but also focused on how the future will shape up with new personalities and new energy.

This outlook is a unifying lens for the list of books we have chosen because every one of these novels is, in some way, negotiating responsibility across time. Not nostalgia or progress for its own sake, but the uneasy space in between when both the past is having influence but the future is forcing its own considerations on us as readers.

We have books steeped in memory and legacy, others that examine how deeply the past imprints itself on the physical self. What happens when the past is distorted? How does trauma and colonial inheritance influence our current day decisions? What do we carry forward? What do we lay down? Which inheritances are burdens and which are gifts? What happens when future paths are infinite and determined by the paths we abandoned?

In 2026, we read across time. And we invite you to join us on the journey. Here’s our reading list:

Love Is Blind – William Boyd

Dark Matter – Blake Crouch

Girls Against God – Jenny Hval

All Our Yesterdays – Natalia Ginzberg

1985 – Dominic Hoey

What We Can Know – Ian McEwan

Soviet Milk – Nora Ikstena

The Frozen River – Ariel Lawhon

Intermezzo – Sally Rooney

Daughters Of The Deer – Danielle Daniel

2025: End Of Year Thoughts

When we talk about the world being global, it’s easy to imagine overwhelming vastness and perhaps feel a little lost in it. When in fact the world is not stretching away from us, it’s coming to us. Wherever we are, we are surrounded by language, food, music, beliefs and histories that originate from beyond our immediate location. We don’t have to travel to experience cultural exchange, instead it happens in our schools, workplaces and neighbourhoods, offering everyday opportunities to stretch our thinking and considerations.

Our senses impose on us a particular kind of knowledge of the world. And they are limited, aren’t they? But what if the world around us is entirely different than our imperfect senses try to convince us?

The Empusium by Olga Tokarczuk

This closeness brings challenges as well as rewards. International events in 2025 have shown us that political decisions, environmental shifts and social movements are not bound by borders. No place is truly insulated from what happens elsewhere. But, alongside the uncertainty this can bring is the possibility of deeper understanding. Exposure, good and bad, to different cultures and ideas can make us more curious and capable of seeing the world from perspectives other than our own.

This is why reading novels that reflect the global landscape matters. Fiction allows us to experience difference without fear, to sit inside another life and recognise both its specificity and humanity.

One man hurried his daughter across the street to avoid us, and when she said that we looked quite normal he muttered, “They’re not like you and me.”

The Book of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey

That thinking shaped our decision to read “around the world” in 2025, our 19th year of bookclub. It’s humbling to reflect on how much has changed since 2007, not just around the world but in our reading group as a reflection of the wider world. Back then, our choices were narrow. We read mostly men, and very little translated or cultural fiction.

By comparison in 2025 every book took us somewhere different. Germany, Poland, Italy, Antarctica, Britain, Palestine, Ukraine, America, Ireland and Morocco. Each author was a compelling guide to their country and culture and provided clear messages on societal pasts and potential futures.

They’d drive at full speed on the road to Azemmour, or fall asleep in the sun high above Casablanca, among the laundry and the giant satellite dishes. They’d wake up to the song of the muezzin summoning the faithful for evening prayer, and all the white roofs would already be orange from the setting sun.

As Rich As The King by Abigail Assor

We also welcomed three new book club members this year. Tessa, Sally and Bridget have brought their own worldly experiences to discussions. Thank you, and welcome!

We ended the year at Brick Eatery, talking through our best of the best. With a broader reading list and a more varied membership there was less consensus than in years past, which felt refreshing. Though, Wild Dark Shore did take the unofficial award for most atmospheric setting, and there were a couple of clear overall favourites. Most importantly, our differences and commonalities prompted lively discussions about what was memorable, what has stayed with us and how our feelings have evolved about some of the titles.

It’s what you all do, in the free world. You waste your freedom and your clear skies on things that don’t matter, like politeness and the perfect lawn. That’s why I can’t go back. I lived in a stupor and now, it’s like, all the colors are saturated. Like someone took electrodes to my eye rods and jolted them. You become like a lizard, where there’s no past or future, where everything’s trained on the present.

Endling by Maria Reva

Here’s some of our thoughts:

Best Cover:

Bridget: Endling

Jodie: The Book of Guilt

Rachel: The Book of Guilt

Sally: Endling

Tessa: Before The Queen Falls Asleep

Best Character:

Bridget: Vincent from The Book Of Guilt

Jodie: Alessandra from Her Side Of The Story

Rachel: Alessandra from Her Side Of The Story

Sally: Vincent from The Book Of Guilt

Tessa: Mother Night from The Book Of Guilt

Favourite Animal:

Bridget: Lefty the snail in Endling

Jodie: Cynthia the dog in The Book Of Guilt

Rachel: The albatross in Wild Dark Shore

Sally: The ponies in The Book Of Guilt

Tessa: Cynthia the dog in The Book Of Guilt

Best ending:

Bridget: As Rich As The King

Jodie: Her Side Of The Story

Rachel: Her Side Of The Story

Sally: The Book Of Guilt

Tessa: The Empusium

Runner Up Best Book:

Bridget: Hum by Helen Phillips

Jodie: Her Side Of The Story by Alba de Cespedes

Rachel: The Book Of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey

Sally: The Empusium by Olga Tokarczuk

Tessa: The Book Of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey

Book Of The Year:

Bridget: The Book Of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey

Jodie: The Book Of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey

Rachel: Endling by Maria Reva

Sally: The Book Of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey

Tessa: Endling by Maria Reva

I could reproach her for having subjected me to that climate of perpetual exaltation which, above all, made me completely devoted to the myth of the Great Love and thus unintentionally led to the painful situation I find myself in today.

Her Side Of The Story by Alba de Cespedes

Pictured: Brick Eatery in Monaco, Nelson

As Rich As The King – Abigail Assor

READ FOR BOOKCLUB

Chosen by Rachel

Sarah is poor, but pretty and French, which gives her standing in Casablanca. Driss is older, quiet and not particularly good looking but he’s rumoured to be the richest guy in the city. Sarah decides she wants a life like his but to get to Driss she will have to cross the gaping divide that separates them. Provocative, immersive, sensual, As Rich as the King is a bittersweet ode to Casablanca.

Home was a falling-down brick building. There was never any hot water … She was about to open the front door when she heard a voice—she knew he’d be here, the little shit … ‘You think you’re better than we are, Lalla Sarah, because you hang out with the rich kids?’ … ‘Of course I’m better than you. I’m French. We’re not the same, idiot.’ As she went inside, she distinctly heard Abdellah hiss, ‘We’re exactly the same.’

RACHEL

● As Rich As The King is touted as a “twisted love story” but I appreciated how it avoided the usual romance markers. Instead it is a layered and nuanced story about desire, class and power. It is also an unorthodox blend of genres, which is something I enjoy in a novel. It moves between a coming-of-age narrative, social critique and psychological study of not just the characters but the city of Casablanca too.

Sarah and Driss work well as figures representative of different factions of Casablanca. Sarah is especially compelling. She is flawed and unsettling, yet feels vividly real. Despite her morally ambiguous thoughts and actions I understood her hunger for a better life and was always rooting for her. While Driss is wealthy, he too is constrained by circumstance and expectation, and the two of them come together in a yin and yang kind of way. The book showed how we are always on the hunt for what we don’t have, as people and nations and societies. I loved it.

SALLY

● In the first analysis, this novel is about love affairs. Primarily it is about a love affair between Sarah and her rich boyfriend Driss. It is also about Sarah’s love and desire for money and to find an escape from her impoverished life on the street. Over-arching all of that, there is a love affair between the author and her native city, Casablanca.

However, closer analysis shows it to be a book about the dynamics of power. Virtually all the characters in the book are trapped by the power wielded over them by others. There are cultural and religious dynamics at play as well as social hierarchies and for Sarah at least, the life she craves is revealed to be just as corrupt as the one she inhabits.

Casablanca as a character all on its own is painted with the colour and depth that you might expect from a native. No holds are barred. We see the dark and the light of it, the glittery and the filthy. I enjoyed it and felt sure of its authenticity. There was much debate (again) within our group about the ending. I choose to feel positive that two people from opposite sides of the tracks can actually break the mould and create a different future to that dictated by society.

BRIDGET

● Set in Casablanca, As Rich as a King is a love story that explores how social power and hierarchy shape the lives of its characters. Each character struggles to find their place within this structured world. Assor’s writing captures the complexity of this world with sharp, often humorous observations, making the story engaging without feeling heavy, as we follow Sarah, who is determined to escape her life of poverty and has no shame in doing what she needs to get ahead. Overall, it’s a well-written and an enjoyable read.

JODIE

● As Rich as the King is a culturally rich novel that pulls you right into Morocco and all its layers. The story takes you on an emotionally complex journey with Sarah, whose choices aren’t always the most ethical, but honestly, I still found myself on her side the whole time. She’s trying to climb out of a world that doesn’t give her many options and that makes her actions feel understandable. The Casablanca scene was one of my favourites, vivid, intense and almost cinematic. I also really enjoyed how the book digs into the class and social divide showcasing how much power and privilege shape people’s lives. I found Rach’s research on the history of Casablanca really interesting and it really helped with overall understanding of the writer’s intentions.

TESSA

● I had a bit of a mixed experience with As Rich as the King. For the first half of the book, the story took its time to get going, and I caught myself growing impatient, waiting for something to happen. Assor’s writing is easy to read but it felt a bit distant at first, and I didn’t immediately connect with the characters. But somewhere past the halfway mark, things shifted for me. The main characters Driss and Sarah began to open up emotionally, and I became far more invested in where their story was going.

What really stood out for me was the setting. Assor brings 1990s Casablanca to life in vivid, almost overwhelming detail. The heat, the food stalls, the noise and chaos of the streets, the incredibly gory ‘Eid’ celebrations, and the stark divide between rich and poor neighbourhoods all combine to make the city feel like its own character. This grounds it in a sharply observed cultural and social landscape. I appreciated this, even though I’ll admit it put me off ever wanting to visit Casablanca.

The themes of class inequality, gender boundaries, privilege, and the cost of ambition are some of the main themes of the novel. Nothing is romanticised, especially not Sarah and Driss’s relationship. I actually liked that it didn’t fit any neat romantic pattern. There are shifting power dynamics and vulnerability in both characters, and I felt it was never one-sided. I found Sarah a compellingly flawed protagonist and not always easy to like. She is opportunistic and calculating at times, yet also vulnerable, observant, and profoundly shaped by her limited choices and circumstance. Her decisions are not always comfortable to read about, but they feel understandable within her social and emotional reality. Driss is similarly layered privileged, yet insecure and emotionally distant.

Overall, As Rich as the King is an atmospheric, and psychologically rich novel that uses a coming-of-age relationship to explore class, desire, and the longing to transcend one’s origins. Its greatest strengths are its evocative setting, bold social critique, and complex characters. By the time I reached the end of the book it had certainly grown on me. The ending is left open to interpretation, which proved a lively topic for discussion at our book club meeting.

Published in French in 2021

Translated into English by Natalia Lehrer in 2023

Pushkin Press

199 pages

Bookerthon – 2025

For our 25th Bookerthon, we hunkered down in Arrowtown, Central Otago, where fresh snow made for great photos against the blue skies and Spring blooms. The setting, as it turned out, mirrored the prose of this year’s Booker shortlist: crisp, clear and alive.

They were alone together, and no one had told her how long it would last. [Flashlight]

What we discovered in our reading was a shortlist of interiority, human fragility, and the small moments that make a life. There were no invented worlds or speculative dystopias here, nor attempts to retell or deconstruct history. Instead, these books turned inward, examining existence and connection.

Historical and political moments do feature but rather than take over the plot they create mood and explanation. History serves as a kind of echo chamber, amplifying the moral, emotional, and spiritual dilemmas of living a human life under pressure.

Every book features a character who is lonely or disconnected, an individual whose sense of place diminishes despite the world growing ever more connected. The characters are alienated yet crave intimacy, and are burdened by expectations. The settings differ, from Cold War Britain to contemporary America to the backstreets of Delhi, but the emotional weather is the same: everyone is searching for meaning within their own solitude.

If you are lonely, you feel ashamed, and the only relief to your shame is being alone, which is what makes you lonely in the first place. [The Loneliness of Sonia & Sunny]

Kiran Desai’s The Loneliness of Sonia & Sunny was nineteen years in the making and follows two Indian immigrants separated by continents yet joined by a shared sense of loss and longing. Their loneliness becomes a metaphor for the way one can be surrounded by others and still feel unseen.

Susan Choi’s Flashlight captures loneliness both literally and emotionally. Her characters are haunted by their pasts and by the aftershocks of war that ripple through generations. The novel’s fractured structure reflects their disorientation with raw memories and years vanishing between chapters.

Katie Kitamura’s Audition takes isolation into another register by questioning the idea of performance and how we want to be seen. It’s a book that kind of watches you back, reminding you of your own solitude and place.

Home, it turned out, had been the perfect preparation for not being at home. [The Land In Winter]

Andrew Miller’s The Land in Winter is probably the most traditional on the list, but also the most complete. Set during Britain’s great freeze of 1962, it traps two couples within a landscape of ice and introspection. The snow isolates them physically, but class, illness, money and silence isolate them emotionally.

Ben Markovits’ The Rest of Our Lives is a midlife road novel with a lonely man obsessed with self-invention at its centre. Tom replays old failures and tests out new versions of himself. He’s a man haunted by the question of what a life comes to when the easy milestones have been met.

David Szalay’s Flesh follows István, a Hungarian man who is always moving but stationary at the same time. He moves through jobs, countries, and relationships without really showing any emotion.

Something uncoiled in my stomach, slow and languorous, and I decided it would be better if I left. [Audition]

Each book is precisely controlled and shaped. Whether 192 or 670 pages long there are no wasted words and a real sense of the author’s control. The books have mostly linear narratives, strong dialogue and intelligent observations. Even their endings feel akin. None rely on revelation. There are no late-stage twists or transformations. Instead, they close quietly, with characters who seem to understand that life continues, albeit it in an altered state.

Is the idea of healing to get you back to the way you used to be or to turn you into something new? [The Rest Of Our Lives]

Szalay’s title introduces another shared theme: flesh. These books are full of bodies damaged, desired, failing and enduring. Their characters are abused, ill, pregnant, grieving, performing. They are trying to inhabit their own flesh in a world that often uses it against them. The body becomes both the battlefield and the evidence of survival, another way to explore what it means to exist meaningfully amid the noise.

For all their seriousness, these novels aren’t bleak. Their introspection offers the consoling thought that being lonely, uncertain or adrift is to be human, and that even in solitude, we are seen.

SUZY:

An absolutely fantastic shortlist, with each novel showcasing an author at the top of their game. Many of the books had a lovely meandering quality to them, luring me in to a gentle state only to then leave me thrown when everything was turned on its head. I was able to completely lose myself in each and every one of them and did not feel like I was reading a book, but rather gaining an insight into the lives, loves and losses of many different people. The Loneliness of Sonia & Sunny was my absolute highlight and I am crossing my fingers for the brilliant Kiran Desai.

After a while he does make one friend, another solitary individual. [Flesh]

RACHEL:

While I had varying responses to the individual titles I liked the six as a collection. It feels like a purposeful selection by the judges, wanting to set to history the tone of literature in 2025. This introspective focus makes for meaningful reading, like really getting to the heart of life and living. As such all these characters are memorable (for better or worse) and I’m sure they will stay with me for a long time.

I read a few of the longlisted books too and to be honest was disappointed some of them did not progress further. Seascraper by Benjamin Wood and Love Forms by Claire Adam were fantastic and would have fit into the shortlist theme of isolation and place. Endling by Maria Reva also studies the meaning of the individual but in an absurdist text. Its surrealism drives home the need for a sense of belonging and in my opinion should have been shortlisted and should have won. Without it to choose from I’ll put my bets on Audition by Katie Kitamura. It’s an intelligent work that lets the reader get involved in the performance of just being and I appreciated the multi-meaning narrative.

The Loneliness of Sonia & Sunny – Kiran Desai

READ FOR BOOKERTHON

The Loneliness of Sonia & Sunny follows two immigrants navigating the quiet ache of isolation in a globalised world. Sonia and Sunny are writers in America, out of tune with their partners and confessing to loneliness and homesickness for their native India. As they become more alienated, they begin to question their understanding of happiness, human connection, and where they belong. Through their intertwined yet separate lives, Desai explores love, identity, belonging and dislocation across continents.

There was so much life in this country that Sunny needn’t bother to create one. His life could be simply looking upon life.

RACHEL

● The Loneliness of Sonia & Sunny is a vast, sweeping book of 670 pages with generations of characters, scenes set in various locations, and global and social events impacting the narrative. However, Desai has cleverly kept the intensity on a select few characters, mainly Sonia and Sunny, and let the support cast, world events and social commentaries swirl around them, impacting and boosting their development. It’s a structure that demonstrates how the small, intricate moments of being human are what really keep the world turning. Few authors could write a book of this scale without making it feel arduous, but Desai has hit the mark. Yes it takes an investment of time to get through it, but I know I’ll never forget this book.

SUZY

● This book is beautiful, sumptuous, heartening and delightful. I completely lost myself in it, and it was paced in such a way that every one of the 670 pages was enjoyable and unhurried. The wait for Kiran Desai’s next masterpiece was completely worth it and I would love to see her take out first place in the Booker.

Published 2025

Hogarth

670 pages

Flashlight – Susan Choi

READ FOR BOOKERTHON

One summer night, a man disappears while walking with his daughter on a Japanese beach. Born Korean, Serk has a complicated relationship with his past. His daughter and American wife become disorientated, facing the challenges of ordinary life all the while grieving for Serk and wondering what really happened the night he vanished. The titular flashlight is a device, flashing in and out of key moments, highlighting atrocities and being a beacon of hope.

The fact – that the flashlight, in falling, landed almost noiselessly in sand – rippled over her like the pale cloud of light on the ceiling. It was not a memory, as Louisa understood memory: a fragmented, juddering filmstrip of image and sound. This wasn’t something but nothing, an absence where a presence was expected. There had been no clattering onto the rocks. There had been no splash in the water. The flashlight had landed almost noiselessly in sand.

SUZY

● Love love love a book where there is such profound learning amongst such a gripping and mysterious storyline. Flashlight opened my eyes to another part of history that I had previously been embarrassingly ignorant of. Many of the main characters in this book weren’t particularly likeable, but the author did such a wonderful job of making them so incredibly human that I couldn’t help but care for them deeply.

RACHEL

● To be honest I DNF’d Flashlight on my first read. The opening chapters hooked me but mid-way I couldn’t work out where the story was heading and my attention began to wane. I did eventually go back to it and am glad I did because at the two thirds point I became gripped, learning about a post-war historical exploitation and its wide-reaching consequences.

The chapters before this move between times and locations, developing each character by detailing their influential life moments. These chapters create a sense of place and show how the immigrant characters became lost in them. So there was worth in those pages, I just wish Choi got to, or alluded to, the best stuff a bit sooner.

Published 2025

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

464 pages

Audition – Katie Kitamura

READ FOR BOOKERTHON

Two people meet for lunch in a Manhattan restaurant. She’s an accomplished actress in rehearsals for an upcoming premiere. He’s attractive, troubled, and young. Who is he to her, and who is she to him? In Audition, two competing but mirroring narratives unspool, rewriting our understanding of the roles the characters play and the truths every person’s individual performance masks.

There are always two stories taking place at once, the narrative inside the play and the narrative around it, and the boundary between the two is more porous than you might think, that is both the danger and the excitement of the performance.

RACHEL

● Audition is a sleek, contemporary and performative novel. It has a simple plot with the twists and surprises coming in the form of narrative structure rather than the characters’ actions. As a reader I felt involved, sometimes lost!, but always deeply involved as if the protagonist was speaking just to me. As an actor she kept changing her performance to influence how people perceived her, and was continually engaging her audience, both fictional and me, the reader. When there was a huge narrative jump in the middle of the book I had to have faith in the author and the protagonist in order to take the leap too. I’m glad I did, the other side was exhilarating. I read the book twice and the re-read was a like a completely new reading experience from the first.

SUZY

● It’s a crying shame that in the midst of frantically trying get through the Booker shortlist I do not have the time to revisit Audition, because I desperately want to. It needs to be read again with a different lens and each sentence picked apart. What initially presents as a relatively simple story is anything but. This is my favourite type of Booker novel and I am in awe of the author.

Published 2025

Riverhead Books

197 pages

Prophet Song – Paul Lynch

READ FOR BOOKCLUB

Chosen by Tessa

Prophet Song is set in an alternative Dublin where a tyrannical government is weaving its way into people’s lives, the rebels are rising up and society is slowly collapsing. It focuses on one family who suffer in many ways and one mother, Eilish Stack, who is trying to hold her family together and to keep on living as normally as possible after her husband disappears, her children rebel and her ageing father begins losing his mind. Complicating her decision-making process is her sister in Canada, who is urging her to leave the country.

History is a silent record of people who could not leave, it is a record of those who did not have a choice, you cannot leave when you have nowhere to go and have not the means to go there, you cannot leave when your children cannot get a passport, cannot go when your feet are rooted in the earth and to leave means tearing off your feet.

TESSA

● I chose Prophet Song as our October Book Club read after picking it up at my daughter’s house and being intrigued after reading the synopsis. I launched myself into it and, apart from the lack of paragraph breaks (which took a bit of getting used to), I initially found it fairly easy going. Then I got halfway through, and I understood why my daughter had found it a challenging read. The intensity just keeps building, and I found I needed to put it down and come back to it, sometimes days later.

I don’t know when I last read a book so dark and moody. It tells of a society’s descent into war, which resonates far beyond the dystopian Ireland where the story is set. I found it unrelenting, draining, and heartbreaking. The style of writing felt intentionally suffocating at times, but that’s probably exactly what Lynch wants the reader to feel. You experience the slow tightening of control, the loss of freedom, and the growing desperation of the central character, Eilish, and her family as their world collapses around them.

I felt the children in the story were very strong characters, and I really felt for them. When Eilish was under immense strain, she didn’t always go easy on them, but she did her best under the circumstances. You could also feel the depth of her love for them and how powerless she felt throughout the novel.

I can’t say I loved Prophet Song, but I deeply appreciated Paul Lynch’s poetic writing, which pulled me into the story completely. On writing the book, Paul Lynch said “why are we in the West so short on empathy for the refugees flooding towards our borders? Prophet Song is partly an attempt at radical empathy.” I think he does that superbly well, and that the novel was well deserving of its 2023 Booker Prize win.

The end of the world is always a local event, it comes to your country and visits your town and knocks on the door of your house and becomes to others but some distant warning, a brief report on the news.

JODIE

● Prophet Song is a powerful and unsettling novel that had me immersed in the chaos a society struggles in the face of civil war. At first I struggled with the run-on sentences and rhythm but as the story progressed I realised this mirrored the turmoil and confusion in Eilish’s mind. The lack of pauses reflects her growing desperation and the suffocating nature of life under oppression.

Although I didn’t thoroughly enjoy the novel it is very thought provoking and highlights the horror thousands of people around the world continue to endure. There’s a truly shocking moment that haunted me long after I finished the novel driving home the brutality of war.

BRIDGET

● Prophet Song is not an easy or comforting read. From the very first pages, the author creates an atmosphere of growing unease, where the boundaries between order and chaos slowly collapse. Lynch does a great job of putting you inside Eilish’s mind. It’s impressive how convincingly he writes from a woman’s perspective. What struck me most was how the character’s clung to fragments of normality, trying to live normal lives when everything was falling apart. There’s something heartbreaking and real about that, the way ordinary life keeps going, no matter how bad things get.

I’ll be honest, this book was tough to get through. It’s relentless, often emotionally draining and I really felt the confusion, fear, and fatigue of living under oppression. But on reflection, I’m glad I read it. Lynch is talented in the way he writes, you feel the characters’ weariness & fear. But what really shines through is the resilience of ordinary people caught in extraordinary times. That quiet human instinct to keep living.

SALLY

● I want to describe this book, set in a dystopian, present-day version of Ireland, as chewy. By that, I mean the author writes without paragraph structure and with no quotation marks around any spoken language. It makes for dense reading, requiring a great deal of re-reading and concentrating to make sense of it. I have tried (unsuccessfully), to read James Joyce and this writing style reminded me of his. Since both authors are Irish perhaps this was a deliberate imitation on Lynch’s part. Some readers will find it very off-putting.

For our bookclub, this book comes hard on the tail of two other books about war-torn communities and although this scenario is fictitious, it could easily be translated to Palestine, Ukraine or Syria. One of the over-riding themes of this book is motherhood and Eilish’s dilemma is whether to be honest with her children and risk crushing their hopes or to lie about circumstances and risk a loss of their trust. The reader follows her journey from stubborn pragmatism to total deflation and acquiescence. It is a painful read.

To quote Eilish’s sister, “History is a silent record of people who could not leave.” Masticate your way through this book for a devastating vision of what can so easily happen. As right-wing politics rise globally, there are many who would do well to read Prophet Song and consider their options.

RACHEL

● I first read Prophet Song in 2023 and found it a harrowing and affecting experience. Some scenes have stayed vividly with me ever since. Going into this re-read I was mentally and emotionally prepared for what was coming which allowed me to focus more on the book’s structure and presentation.

I loved the propulsive, rolling narrative that felt both oppressive and compelling. The absence of punctuation and paragraphs made me feel like a fly on the wall in this home, listening as people talked over one another in heightened and whispered voices. The characters are utterly believable, and I kept thinking this could happen to any of us at any time. The language is intelligent and observant, and adds further nuance to an already layered story. It’s an extraordinary work that I wish everyone would read, though I know not everyone could endure.

Published 2023

Oneworld Publications

259 pages

Flesh – David Szalay

READ FOR BOOKERTHON

The story of István, a Hungarian teen who lives with his mother and is subjected to a traumatic event. From there we bear witness to a collection of intimate moments set over years, chronicling the demands of life for an everyday person who is unsure what role he is meant to play.

And all that burgeoning physicality is held within yourself as a sort of secret, even as it is also the actual surface that you present to the world, so that you’re left absurdly exposed, unsure whether the world knows everything about you or nothing, because you have no way of knowing whether these experiences that you’re having are universal or entirely specific.

SUZY

● Flesh is the story of a life that has moments of being completely ordinary and then very unusual. It feels hard to explain my thoughts on the book without talking about a defining event that occurs at the very start. It caused me to wonder which of the protagonist’s life choices were in response to this. Essentially, I second-guessed my way through the entire novel.

It’s testament to the skill of the author that as a reader I had an entirely different dialogue running through my head as I processed what was happening on the page. Flesh had moments of hope, but overall was a sad story, and one that I feel richer for having read.

RACHEL

● Flesh is an existential book that grew on me the more I read it. István demonstrates the male experience via roles he never asked for. He’s meant to be strong, protective, ambitious, loyal, all the usual markers of masculinity, but he doesn’t seem to know what any of that really means and instead is just reactive. He’s manipulated and manipulative, a saviour one moment and careless the next. He’s an interesting case study.

The book is steady, but kind of monotone and flat. That sounds like a criticism but that passivity and numbness is what builds István’s character. Even his constant response of “okay” irritated me at first but then I came to see it was indicative of him as a character and how he chose to pacify without agreeing. I can’t help but compare Flesh to one of the other Booker shortlisters which also attempted to write about the male experience. In doing that I see how accomplished Flesh is, detailing a man’s life lived in the flesh but burdened by external expectations.

Published 2025

Scribner

368 pages

Recent Comments